05/2021 architecture & interior

When cyclist Klaus-Jürgen Grünke of the German Democratic Republic was awarded Gold at the Montréal 1976 Olympic Games, nobody inside the brutalist velodrome could have guessed that one day the venue would become a calming nucleus of biodiversity. Through a KANVA redesign, the concrete fortress of the Biodôme science museum now strikes a harmonious balance between architecture and a biosphere.

The structure was originally conceived by French architect Roger Taillibert to stage the Olympic Games. But the building also had to withstand the prolonged Québec winters. After the sporting events, Montréal transformed the site into a cultural landmark for the city. The first phase opened in 1989, with the science museum following three years later. Considered the "jewel in the crown of a consortium of facilities that collectively account for the most visited museum spaces in Canada," the museum was in dire need of a renovation and this trust fell to Rami Bebawi and his studio KANVA.

The entry tunnel of the Biodôme features a very subtle floor incline, intended to slow the pace of movement through a compressed white passage and to void the mind for fresh sensory input. (Photo: Marc Cramer)

The renovation endured seven years of construction delays, postponed re-openings, and canceled contracts on a similar scale to the BER airport. Bebawi and co-founder Tudor Radulescu had originally won an international architectural competition for their interpretation of the space. They were commissioned for the $25 million (€16,9 million) projects by Space for Life, the body charged with overseeing operations of the Biodôme, Planetarium, Insectarium, and Botanical Garden. As a local architecture firm, they were renowned for meaningful projects that extend beyond the boundaries of architectural shapes and forms. But their study of the structure's complexity allowed for a radical rethink of its core.

“Our mandate was to enhance the immersive experience between visitors and the museum’s distinct ecosystems, as well as to transform the building’s public spaces,” notes Bebawi. Once the five ecosystems were architecturally divided and felt disconnected from one another. The KANVA intervention in collaboration with NEUF architect(e)s embraced the original skylights of the arch structure. The segregating low ceilings were disassembled, allowing each ecosystem to be flooded with an abundance of natural light from above. This brought together the Tropical Rainforest, Laurentian Maple Forest, Gulf of Saint Lawrence, Sub-Antarctic Islands, and the Labrador Coast for the first time. “In doing so, we proudly embraced the role that the Biodôme plays in sensitizing humans to the intricacies of natural environments," explains Bebawi.

This is particularly crucial to the practice in the current context of climate change and the importance of understanding its effects. “Before you can even begin to design in an environment with living species all around you, education and a notion of humbleness are required,” explains Bebawi. “We take basic assumptions about ourselves for granted when we design for other human beings, but designing for an otter or a sloth requires that you re-educate yourself.”

At the central core, smaller slits in the living skin, called eco-transits, lead them towards the ecosystem entrances. As automatic doors at the end of the eco-transit open into the ecosystem, it remains visually obstructed by a curtain of beads. (Photo: Marc Cramer)

Through delicate modifications to harness the structural heritage, the museum has been brought into a modern context with a sense of biblical light throughout that alludes to a sense of infinity. Housed within the sensorial skylit dome are 250,000 animals and 500 plant species, with these conservation habitats receiving just as much attention. The linear focus of the internal atmosphere was soliciting senses, relegating sight to the end of the line behind sound, smell, and touch. From the calming lobby hall, the undulating living skin funnels visitors into a 10-meter tunnel leading to the central core, where they can explore five ecosystems. “It’s a very powerful tool, half a kilometer in length and rising nearly four stories,” explains Bebawi. “It’s extremely emblematic of the space, and the white purity beautifully highlights and contrasts the original structural concrete.”

The biophilic skin was a feat of structural engineering and overcame complicated interior obstacles. The designers choose to curve and stretch the skin around a bowed aluminum structure, using tension, cantilevering, and triangular beams for suspension, and is itself anchored to a primary steel structure. One of the most fundamental pillars of the redesign was enhancing the space's ability to reconnect people with the environment. Bebawi believes there is "a delicate balance in nature. There is a notion of time and cycles. There is a game of inclusivity and selectivity." He asks whether there is a need to "dilute the boundaries between us and them, humans and animals," to which he considers "the most essential responsibility of contemporary architecture." He argues that our distancing from other living species has not only harmed the environment but has also denatured us.

During the design process, the team would often turn towards notions of sentient architecture or sensorial design. "Architecture is a mechanism to solicit senses; sound, smell, touch, taste, and sight. We share senses with all living species. They anchor us. They affect our instinctive behaviors," he explains. The species are shown through conservation, not shows to the public. The hope is to continue raising awareness of environmental destruction, issues, and the relationship between plants and wildlife.

KANVA’s approach seeks to re-question and transform the built environment, and the firm approaches each project as an opportunity to tell a story and to expand the scope and dialogue between art and architecture. (Photo: Marc Cramer)

The Biodôme's new lease of life is an inspirational model for many former Olympic spaces. We ask Bebawi what he hopes the redesign can teach cities about their monumental and brutalist structures, he replies, "Olympic structures are mythical. They remind me of Universal Exhibition Pavilions, although they are more permanent rather than ephemeral. They are a collective effort of innovation and celebration and yet they live for a period of two weeks, with a single function." He ponders many questions about the durability of an Olympic legacy. "Perhaps a starting point could be to address new Olympic buildings as entities that will change after the Olympics. Perhaps a giant football stadium could be modularly deconstructed into several smaller stadiums to be scattered throughout the host city after the international events," he says, "or perhaps their design could account for a future wider array of functions to avoid the abandoned structures presently scattered in cities around the world."

With the recent recipients of the Pritzker award, Bebawi sees a rise in notions of rehabilitation, repurposing and salvaging of existing buildings. To him, the science museum is an example of such notions. To Bebawi, the Biodôme is "a precious dichotomy that speaks of balance and living entities cohabitating." He concludes by saying "the massive structure is maintained and celebrated. Yet it does not prevent us from inhabiting it with a delicate natural insertion," he implies. This stunning redesign embodies many of his philosophical approaches to design, humanity, and nature.

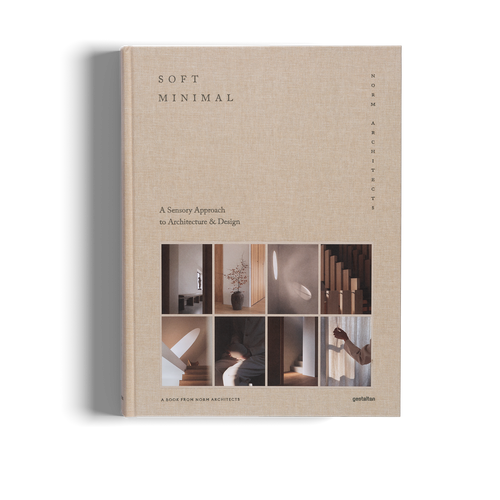

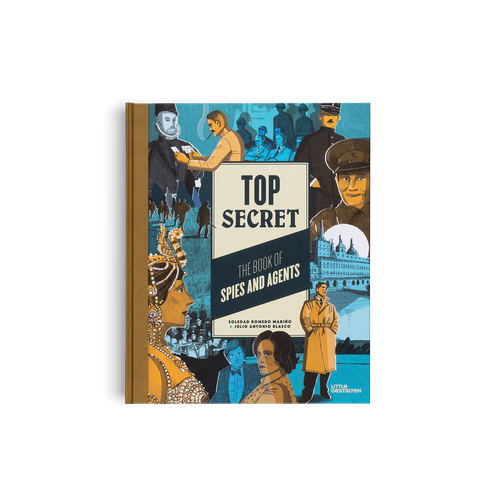

Explore breathtaking architecture and aesthetic driven interiors through a selection of gestalten titles.