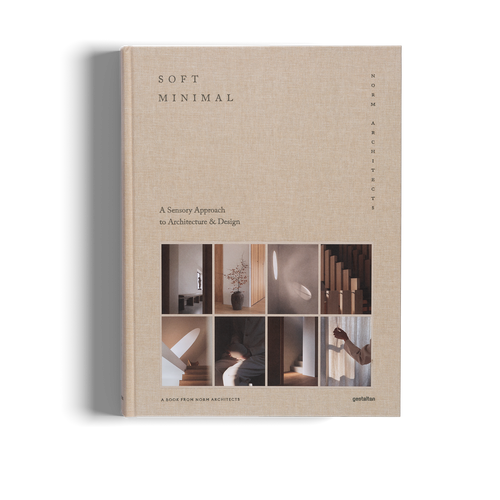

04/2022 visual culture

To see the natural world through Harper’s eyes is to revel in the purity of color, form, and balance, providing his audience with thousands of pictures that allow the viewer to inhabit this point of view. As a young man, he worried about whether he could become the kind of artist who comments on the world in a singular, sincere way. As the pages of Wild Life will show you, Harper did become such an artist, spending a lifetime delighting others with his comment.

Wild Life, created in collaboration with Brett Harper, the artist’s son, and illustration expert, Margaret Rhodes, is a vast collection of works originally created as posters, magazine covers, murals and others.

(Photo: Charley Harper Art Studio, Wild Life)

Brett and Margaret sat down to discuss their process in creating this definitive monograph, favorite pieces from his collection, and everything in between.

Brett to Margaret: What was your most memorable moment while working on Wild Life?

M: My visit to Cincinnati, easily. Before that trip, I had conducted several interviews and been sifting through Charley’s many, many prints. I started to develop a stronger sense of feeling like I knew Charley, or at least knew what he was about. But in Cincinnati—as you know, since you showed me around—I was able to dig through drawers and folders, read through old correspondence between Charley and his fans or publishers, and look at sketches and notes on napkins.

(Photo: Charley Harper Art Studio, Wild Life)

And, of course, we spent time at Charley and Edie’s incredible midcentury home in Finneytown. It cast everything into sharper relief. Charley was so intentional about everything he created, but remained approachable, kind and inquisitive throughout his career. He would write thoughtful letters to people who bought his art through Ford Times, or send long dispatches about field surveys to his contacts at the National Park Service. He really cared about the details.

(Photo: Charley Harper Art Studio, Wild Life)

Margaret to Brett: It’s probably hard to choose, but do you have a favorite piece of art—or period of work—of your dad’s?

B: Jesus Bugs, a large acrylic painting of what are actually insects known as water striders, is one of my favorites. Perhaps because it was so important to Charley. Done in 1960, it was his celebration of afternoons leaning over the creeks of his native West Virginia, watching the sun cast shadows of the bugs onto the bottom. The title comes from the nickname for the water striders - the comparison to the Biblical Jesus, who walked on water as they also appear to do.

(Photo: Charley Harper Art Studio, Wild Life)

Brett to Margaret: How would you describe the significance of Charley’s work within the art world?

M: I think it puts a name and a face to a style that’s kind of been in the water for a long time. Speaking very broadly, in the early-aughts there was a big revival of mid-century modern design, furniture, fashion, etc. Charley’s work is quintessential to that era, but outside of Cincinnati, or certain illustration or graphic arts circles, his name wasn’t known in connection to that period.

(Photo: Charley Harper Art Studio, Wild Life)

Margaret to Brett: What is your fondest memory of Charley? And of Charley and Edie together?

B: I will never forget how angry Charley got twice, when he couldn’t figure out how to proceed with his art. Once, he sought out a sledge hammer and pounded it on the family Ford station wagon under the car-port next to his studio. Another time, he was stymied by the printing of his serigraph, Cool Carnivore. All he could think to do was to rip apart individual prints with his hands, then dance and stomp on them with his feet.

I remember Charley and Edie sitting peacefully on the porch swing under cascades of purple wisteria.

(Photo: Charley Harper Art Studio, Wild Life)

Brett to Margaret: After digging into the archive, what influence do you think Edie had on Charley’s work? And how can you see their relationship reflected in the pieces he created?

M: After getting to read their letters to each other—from the early 1940s and during World War II—it feels obvious that Edie mostly influenced Charley by encouraging him to pursue art, full stop. It wasn’t an easy choice to choose art as a career back then (and it still isn’t now) and Charley definitely had doubts. But being seen by Edie made it possible. Edie was a different kind of artist than Charley—more experimental, looser in her aesthetic and subject matter—but she was such a true artist at her core, and I imagine that eliminated any doubt about whether art was a worthwhile pursuit or not. Looking at their work later, it’s harder to say whether Edie influenced Charley’s style, because Charley was so committed to “minimal realism.” But you can tell they were both charmed by the same subject matter, from cats to birds to racoons. It seems like a very wholesome back-and-forth that would dip in and out over decades of being together.

(Photo: Charley Harper Art Studio, Wild Life)

Margaret to Brett: How do you want Charley to be remembered? Not just as an artist, but as a conservationist and community member?

B: Charley will be remembered for his unique style, which in time he gave a name: “minimal realism.” He could paint anything in any style. But minimal realism was what held his interest until the end of his career. He used drafting tools, drop compasses that he deftly handled even in his 80s, and never used a computer. He should be recognized, too, for his technical proficiency in pushing the limits of hand-pulled serigraphy under primitive conditions. He created over 50 posters for non-profit organizations. He was generous with his time to school children, always willing to speak to elementary grade classes. He was always happy to take a break and spend time with my mother and me. He always had several natural history books on his bed-stand at any given time. He never let on that he cared for the family dog, Dusty, but cried when he buried him.

(Photo: Charley Harper Art Studio, Wild Life)

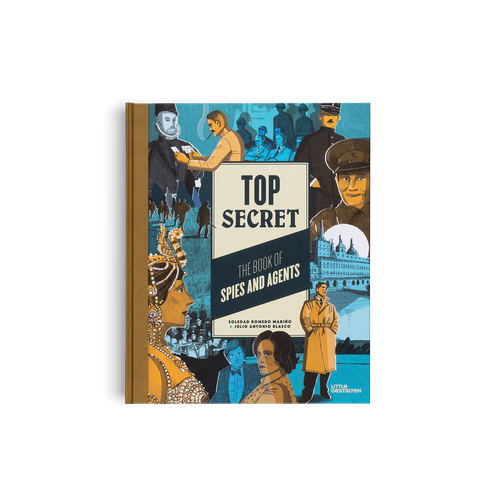

Wild Life offers a rare glimpse into Charley’s private and creative universe. Telling the story of his life and of his masterpieces, this latest gestalten title is essential for enthusiasts of the American master and for those interested in mid-century visual culture.