02/2021 architecture & interior

While preparing for another day of working from home on the dining table or escaping to the bathroom to take a zoom call in private (often the only room with a lock away from children), you might unconsciously be partaking in the next Industrial Revolution. Be it for better or worse, the pandemic has changed our relationship with work, space, and architecture. Over the course of a year, the remote work revolution has created a gaping crater between the quality of life in cities and how we want to interact with the buildings we live and work in.

The population of London is set to decline for the first time since 1988, with the number rumored to shrink by 700,000. The decline of America's coastal superstar cities is already in progress. Migration trends point to people leaving San Francisco, New York, and Los Angeles in droves for Florida, Georgia, and Arizona. Many are arguing remote work could transform the residential geography of today's cities like the highway did seven decades ago. Cities will either spread out to the suburbs or residents will migrate in search of sun and space. Parisians have been fleeing to Casablanca, Londoners to the Algarve, and Bostonians to Southern states. These migration trends could spell troubling times for certain cities and their infrastructure, but they could also promise new opportunities and possibilities to others.

Green in form and function, Henning Larsen designed a campus the French International School that sets an example in sustainability. The building façade optimizes the local climate and decreases energy consumption. The brise-soleils entirely removes the need for blinds or curtains and enable a clearer glass to be used, thus providing a more natural color of daylight in interior spaces. (Images: Philippe Ruault)

The age of the internet started in the 1980s, but it took a pandemic to digitally resettle people to a cloud-connected database. This won't result in the death of the traditional office, but it has shown companies that adopting flexible conditions can have a positive impact on mental health. Salesforce, San Francisco’s largest private employer, will permanently allow most workers to stay home for two or more days a week. Google and Microsoft are also making similar pledges, which implies that the next Silicon Valley could be anywhere and everywhere. This could result in a domino effect across various fields and countries, paving the way for new working patterns or permanent home office roles.

The pandemic is changing how we perceive cities, but it will also likely alter the way we interact inside of them. “Tuberculosis helped make modern architecture modern,” the Princeton professor Beatriz Colomina writes in X-Ray Architecture. As a consequence of the disease's fear, the Modernist movement stirred toward clean and clear spaces to eradicate dust and hidden bacteria. In a post-pandemic era, architecture will undoubtedly adapt to new human behavior and needs. Danish architectural studio Henning Larsen started a dialogue around design in a post-pandemic world last year, with two architects exploring ideas around the kind spaces of spaces we will want to live in and work in after the pandemic. With vaccinations showing a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel, Lead Design Architect Franck Fdida and Kasia Piekarczyk share their thoughts on what tomorrow's architectural landscape could look like.

How do architects play their historical role today concerning challenging architecture for the future?

Kasia: By watching, reading, listening, and learning. Something that we have to keep in mind about architecture is that the field won’t change until we do. But considering the time necessary from the concept to construction, at any given moment we are already shaping the architecture of the future. One thing is clear, this is not a time to sit idle, rather one of transformation. I feel lucky to practice architecture in times that are on the one hand complicated and challenging but the other inspiring and daring.

Because of the global pandemic we were all suddenly pushed off the beaten track by something unexpected, which ironically highlighted other problems we already knew about. Unsustainable architecture and urban planning put huge pressure on the environment. This isn't news. We have already seen this in the past, albeit on a lesser scale.

Franck: By discussing and collaborating with everyone involved in the architectural process, especially public entities. The mighty architect with extensive decisional powers is long gone. To shape our future, cities have an enormous role to play now, and architects need to guide them on the right path. The examples of “reinventing Paris” and the C40 show how much influence cities can have to push everyone in the building sector to challenge today for a better tomorrow. From more sustainable regulations to building in wood or providing generous green spaces, public authorities need to take the front seat!

Inspired by the rich landscape of the North Dakotan Badlands, Henning Larsen married Theodore Roosevelt’s legacy with the community of Medora. After his mother and wife passed within hours of each other in 1884, Roosevelt returned to Medora from New York, and this experience transformed him. Henning Larsen + Nelson Byrd Woltz recreated this journey, and their architectural vision is a homage to the landscape and community that paved the way for his civil icon status. (Renders: Henning Larsen)

What can be achieved in the short-term versus long term?

Kasia: Short-term solutions allow us to rapidly test ideas, assess what works and improve for long-term implementation. Some quick fixes will remain temporary as they merely solve problems that will eventually go away. That includes restrictions regarding social distancing, the number of people using spaces together, disinfecting printer buttons, etc.

In my view, the long-term solutions will result from a new discourse taking place which will redefine the spaces for this type of disruption in the future. For instance, let’s consider the workplace. Should we rent less office space if people can work remotely? Or will a workplace of the future transcend desk-work to become a space for assembly and exchange of opinions? Is it better to work in a tower and depend on an elevator, or rather in a lower building that is comfortably accessible by walking? Apart from deriving from a pandemic, these are interesting and relevant considerations. All of those questions stir up urgent discussions today; the answers will shape the future.

Franck: In the short-term, we witnessed how flexible we were to adapt to a digital solution to continue our daily working tasks. From social distancing, the entire world switched in an instant to digital closeness. But there is already a lot to learn from the past year's experience. I don’t believe that this way of working remotely without physical collaboration and social interaction will sustain for much longer. We are currently using a smart but not sustainable fix to our problem. It is especially relevant in architecture and more generally in the creative industry where concepts are born from confronting ideas, sketching on a big board, and having intense brainstorming. This missing link cannot be entirely fulfilled by smart digital solutions–the physical interaction cannot be digitized. A long-term solution still needs to be found!

The Wave is a project that redefines the overwhelmingly flat landscape of Denmark through five peaks. While crossing over the Vejle Fjord Bridge, The Wave’s distinctive silhouette commands the view. It is the foundation for a revitalized waterfront, but also an architectural tribute to the local landscape, establishing a new visual identity for the town. (Photo: Jacob Due)

In case the current situation persists for a long time or we face a similar pandemic soon, are there ways that architecture and homes can be more than a haven and cater to the mental and physical demands of isolation?

Kasia: The problem is that a haven cannot be a haven if you work there every day and the other way around. There are ways of dealing with this issue, for example through space division and zoning. But honestly, in terms of mental health, I think there’s a limit to what design can do if you are alone and confined to one space for an extended period. That is because even great spaces cannot fulfill the need to socialize, roam freely or be in nature.

Although, I think that there are lessons that we can learn from this when designing homes, for example, how crucial it is to provide a connection to the outdoors. Anything from a vista from your balcony to physical access to shared semi-private gardens available to a small group of people.

Franck: On a personal note, I never thought I will need a proper office space at home before the pandemic. I was used to my comfortable open space at work and would avoid bringing work home. Sharing the same space with your partner and/or children can have a great impact on your work balance, concentration, and production. I guess the future of living will see much more focus on creating office niches at home or potentially co-working spaces for the residence like a shared gym, laundry, or swimming pool.

Because it might be difficult to offer outdoor space and large homes to everyone, the solution on the mental and physical demand might find its resolution in the way we approach the cluster. We could extend this isolation to your floor or building block. Designing the future of living with shared commodities for a specific cluster will provide daylight, nature, and other activities why being isolated. It could also strengthen the sense of community and relation between neighbors.

Henning Larsen’s winning design for Seoul Valley is a mixed-use development that merges the city’s global commercial profile with an ecological return to downtown pedestrian life. The project hopes to reintroduce public life into the center of the city, free from traffic. The vision focuses on public comfort, greenery, and local tradition. (Renders: Henning Larsen)

How would you describe the dwelling of the future?

Kasia: Every time I imagine the future I reflect on comparable dilemmas of the past. There are still centuries (I hope!) before Homo sapiens evolve to Homo Deus, as author Yuval Noah Harari predicts. Until that happens, I feel safe to assume that we will continue to have similar needs, hopes and bodies as we do today, and so our dwellings will need to meet similar expectations. To this inevitably we need to add a technological layer, more and more integrated into our homes.

What I think will be crucial, is not this or that particular building type, but rather the composition of them on an urban scale. In an era of remote work, home food delivery, and online yoga classes we need to make sure that people have a reason to go outside to interact in analog. What will define the dwelling in the future is the public spaces in between.

Many cities (NYC, London, Berlin, Paris) have hollowed out with the absence of tourists and central business workers. A movement to reclaim public spaces like streets, squares and affordable housing is underway. How do you see current human needs shaping post-pandemic cities of the future?

Kasia: I don’t see it as public spaces or squares being hollowed out, at least that’s not the experience from spending most of the pandemic in Copenhagen. On the contrary, public spaces were being used more often and appreciated even more so than usual.

At the same time, I know that many cities or countries reacted differently, and people were discouraged from using public spaces. In Warsaw, where I’m originally from, there was a temporary ban on the city's parks and forests. I drew a lot of balance and comfort in the simple fact that I can go out for a walk, especially in the first months of the lockdown.

In a fear of spreading the virus, people in Warsaw were confined to four walls, without a possibility of finding refuge in nature. It quickly turned out that this hasty regulation originated in panic and misinformation, and achieved rather the opposite of the assumed results.

There is however a general activity drop in specific areas in many cities, which is more complex to explain than through a restrictive movement ban or closed business premises. The pandemic unscrupulously exposed hidden issues of the monoprogramic areas of all cities. This, among other things, made many public spaces inaccessible in a sense of not serving any communities.

The way I see it, as people, we will always need to create communities: to gather, to exchange, to laugh, talk, and learn, and for this, we need public spaces that work regardless of the current geo-health situation.

Wolfsburg Connect is the vision for a new urban district that focuses on sustainable mobility options, green public spaces, and livable streets replacing an underutilized and disconnected previous site. Across the canal from the Volkswagen headquarters, the aim is to breathe new life into a desolate site and create a space centered around greenery and pedestrians. (Renders: Henning Larsen)

What is the mission of architects in this new post-pandemic era, especially with climate neutrality?

Kasia: At Henning Larsen, we base all of our work on the care for the environment and consider the challenges of building sustainably very seriously. A global pandemic is a shock to the system (to all systems) which uncovers all the uncomfortable truths about how we, as a species, use the resources available to us. Unimaginable became reality, and it is grim.

According to IEA, the buildings and construction sector accounted for 36% of final energy use and 39% of energy and process-related CO2 emissions in 2018, globally. I hope we can use this moment as a proverbial reset button. As architects, to speak louder and clearer among ourselves, our clients, and collaborators that we are a party with a huge responsibility regarding achieving the climate neutrality goals in the post-pandemic future.

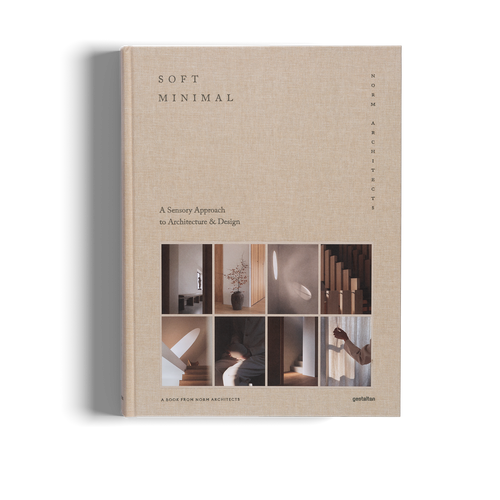

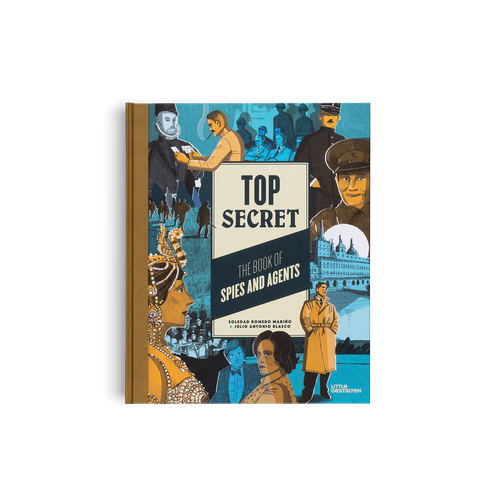

Discover a selection of gestalten architecture & interior titles that feature prominent movements in design and the figures that mastered their craft.